Before Soundscape ecology read about acoustic ecology Wrightson_2000

Introduction

Soundscape ecology represents a multidisciplinary field that examines the complex relationships between organisms, environments, and the acoustic signatures they create and respond to. This emerging science studies how sound sources—from natural phenomena to biological organisms to human activities—interact to form distinctive acoustic environments that affect ecological processes and human experiences. The field has evolved significantly since its formal inception in the late 1970s, with pioneers like R. Murray Schafer and Barry Truax establishing foundational concepts that continue to guide research and practice today. While initially focused on documenting and preserving natural soundscapes, the discipline has expanded to address growing concerns about noise pollution, biodiversity monitoring, and the use of acoustic information in conservation. The field maintains strong connections to creative practices, with sound artists increasingly incorporating ecological principles into their work and developing innovative approaches to raising environmental awareness through sound-based art.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of soundscape studies and their significance, please view the accompanying video.

Foundations and Background of Soundscape Ecology

Soundscape ecology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline in the late 1970s, though its conceptual roots extend further back. The term “soundscape” first appeared in the “Handbook for Acoustic Ecology” edited by Barry Truax in 1978, marking an important moment in the field’s formalization1. While initially used somewhat interchangeably with acoustic ecology, soundscape ecology has developed its own focus and methodological approaches. Acoustic ecology, stemming from the work of R. Murray Schafer and his colleagues, primarily emphasizes human perception, cultural dimension of sound and experience of sound environments, whereas soundscape ecology takes a broader ecological perspective1.

The development of this field coincided with growing environmental awareness and technological advances in recording equipment, allowing researchers to document and analyze sound environments with unprecedented detail. The scientific study of soundscapes has been driven by increasing recognition that acoustic environments provide critical information about ecosystem health, biodiversity, and the impacts of human activities on natural systems. In recent years, standardization efforts have helped consolidate the field’s terminology and methods, including the International Organization for Standardization’s definitions related to soundscape in 2014 (ISO 12913-1:2014)2.

Soundscape ecology represents a response to the changing acoustic environment of our planet. As human-generated sounds have increasingly dominated many landscapes, researchers have documented the ecological consequences of these shifts. The preservation of natural soundscapes has consequently emerged as a recognized conservation goal1. This reflects an understanding that sound is not merely an incidental feature of environments but a fundamental aspect of ecological systems that deserves protection alongside visual landscapes and physical habitats.

Key Components and Terminology of Soundscape Ecology

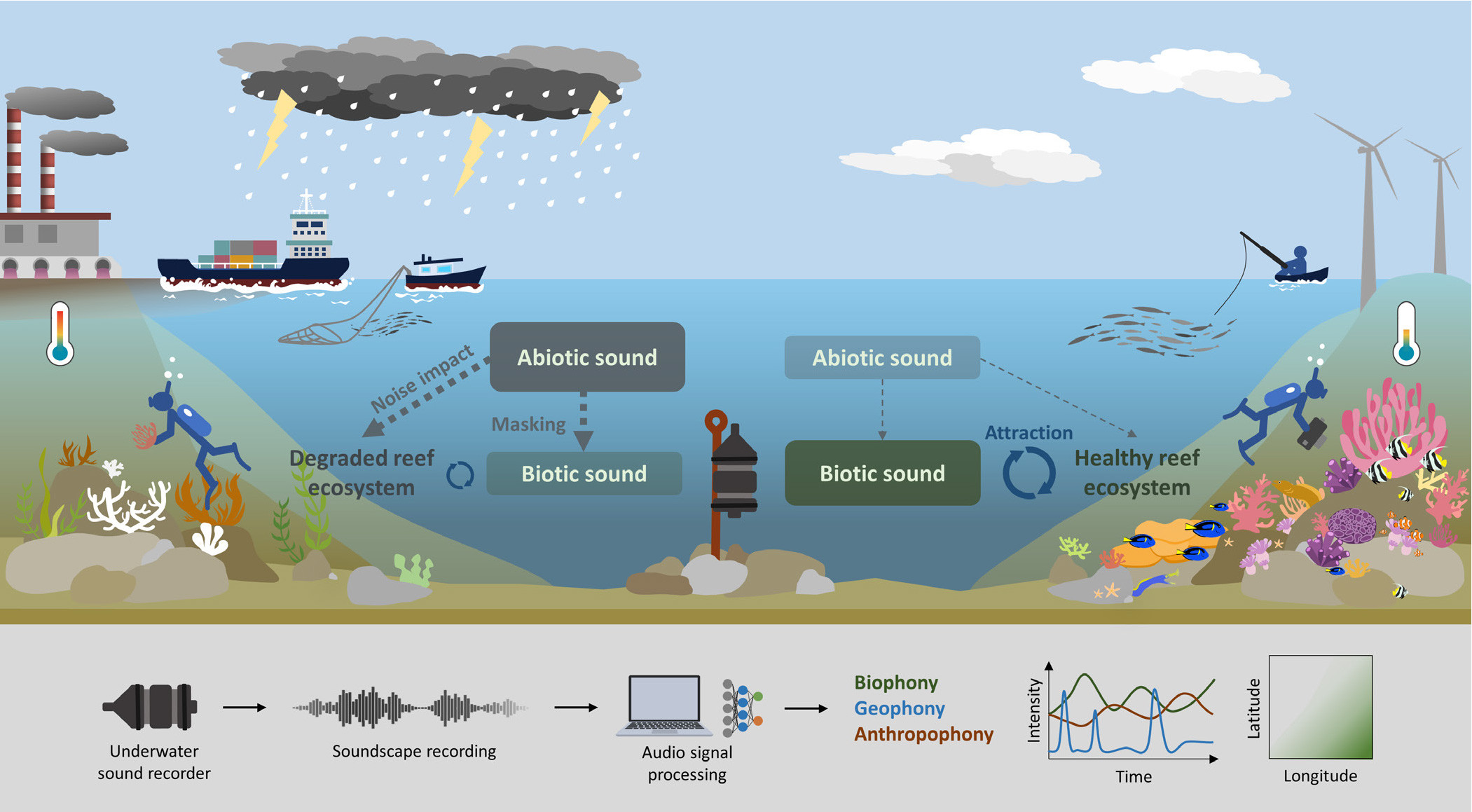

Soundscape ecology operates on the premise that acoustic environments can be analyzed by categorizing sounds according to their sources. These sources are typically divided into three fundamental components that together comprise the complete soundscape of any given environment.

Blank

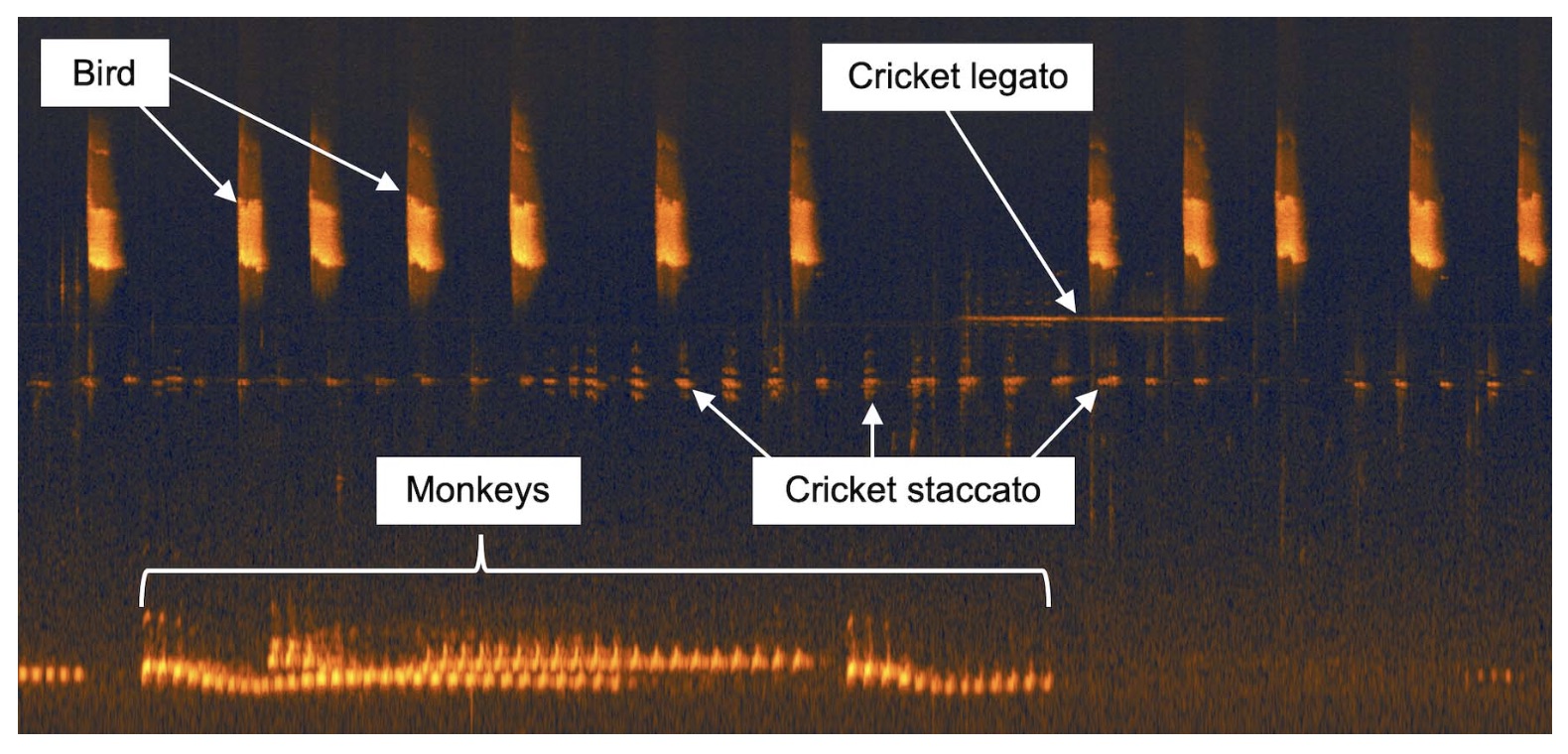

The first category, biophony, encompasses all sounds produced by living organisms other than humans, including bird songs, insect calls, amphibian choruses, and mammalian vocalizations123. These biological sounds often form complex patterns that reflect ecological relationships, seasonal changes, and evolutionary adaptations.

Blank

Biophony of the subtropical rainforest in Cát Bà, Vietnam, source

The second category, geophony, refers to non-biological sounds generated by natural physical processes such as wind, water, thunder, rain, and geological events123. These geophysical sounds create the background acoustic conditions that biological organisms have evolved within and adapted to over millions of years. They establish rhythms and patterns that often influence biological activities and have shaped the evolution of communication systems in many species.

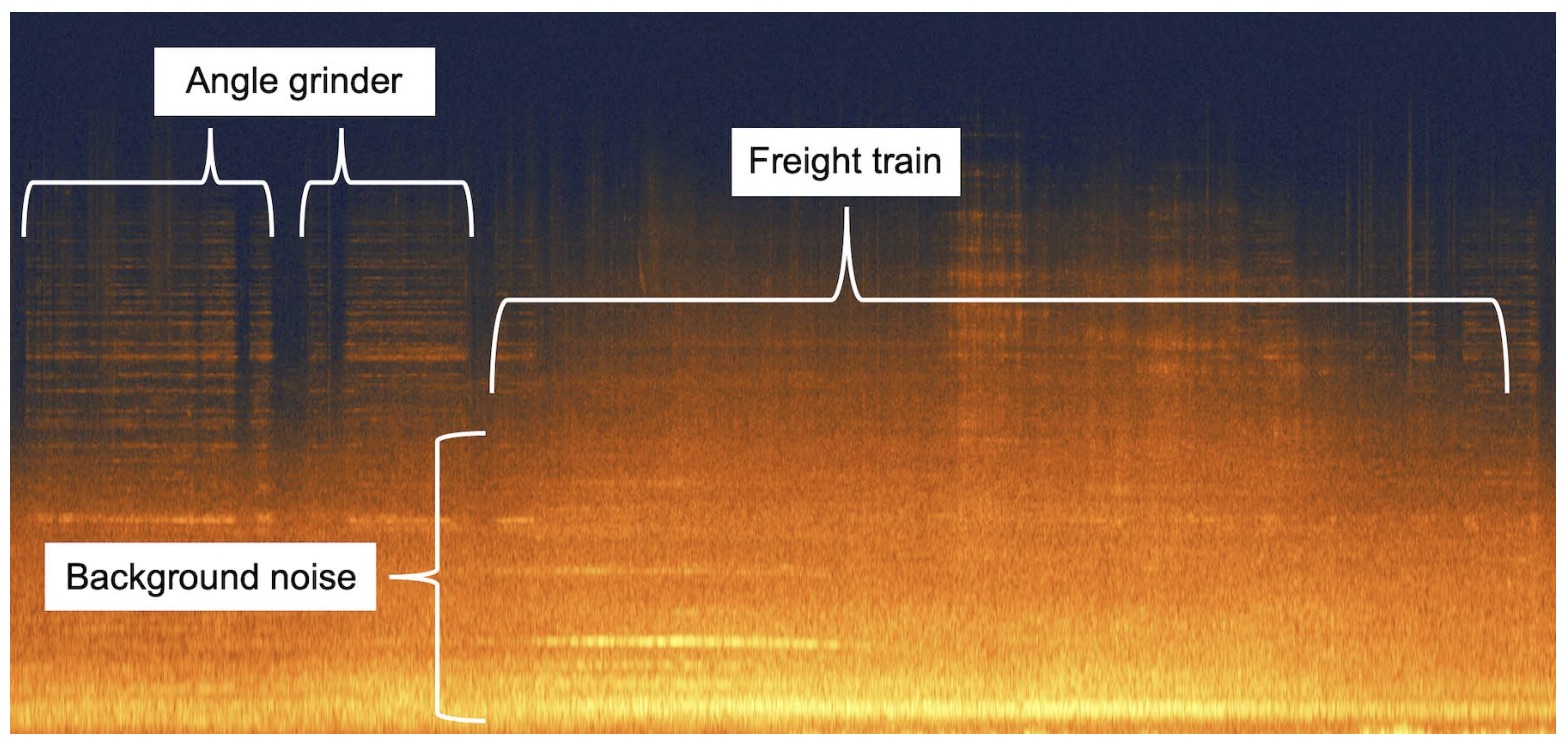

The third category, anthropophony, includes all sounds produced by human activities, from speech and music to industrial noise and transportation sounds123. A significant subset of anthropophony, sometimes termed “technophony,” consists of sounds generated by mechanical and electronic technologies. These human-generated sounds have increased dramatically in both geographic extent and intensity over the past century, leading to growing concerns about noise pollution and its impacts on both human and wildlife populations. Research has documented that this “overwhelming presence of electro-mechanical noise” can produce negative effects on a wide range of organisms1.

Blank

Soundscape Bochum city, source

Understanding these three sound sources and their interactions is central to soundscape ecology. Researchers analyze how different sound components overlap, mask, or influence one another, and how these acoustic relationships reflect and affect ecological processes. The field employs various methodologies, including recording devices, audio analysis tools, and traditional ecological approaches to study soundscape structure and function1.

Pioneers and Notable Figures in Soundscape Ecology

Several visionary researchers and artists have shaped the field of soundscape ecology through their pioneering work and conceptual contributions. R. Murray Schafer, a Canadian composer and environmentalist, stands as perhaps the most influential figure, having popularized the term “soundscape” and developed many of the field’s foundational concepts23. In his seminal work, “The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World,” Schafer explored the importance of preserving natural sounds and their role in defining our sense of place. He also introduced the concept of “ear cleaning,” which involves actively listening to environmental sounds to enhance sonic awareness4.

Barry Truax, who edited the “Handbook for Acoustic Ecology” where the term “soundscape ecology” first formally appeared, has made substantial contributions to the field’s theoretical framework1. His work has helped establish the connections between acoustic communication, sound design, and ecological understanding. Another significant contributor, Bernie Krause, has devoted decades to recording and studying natural soundscapes worldwide, developing the concept of the “biophony” and documenting changes in acoustic environments over time4.

Hildegard Westerkamp has explored the use of sound in artistic expression and environmental activism, bridging scientific understanding with creative practice4. Michael Southworth, who originally coined the term “soundscape,” brought attention to the acoustic dimensions of urban planning and design5. Composer Pauline Oliveros contributed a neurological perspective by defining “soundscape” as “All of the waveforms faithfully transmitted to our audio cortex by the ear and its mechanisms”2.

More recently, Bryan Pijanowski has advanced the field through his comprehensive work “Principles of Soundscape Ecology,” which outlines the discipline’s foundations, key concepts, methods, and applications6. His research has helped establish rigorous methodological approaches and expanded the field’s application across terrestrial, aquatic, and urban environments. Together, these pioneers have created a rich interdisciplinary foundation that continues to inspire new generations of soundscape researchers and practitioners. İpek Oskay is a prominent researcher in Türkiye specializing in sound ecology. Further details regarding her scholarly work can be accessed through the provided links (+90 Interview, Articles, IG Profile).

The World Soundscape Project: Documenting Acoustic Environments

The World Soundscape Project (WSP) represents one of the earliest and most significant organized efforts to study, document, and preserve soundscapes. While specific details about the project are limited in the search results, contextual information suggests its importance in the development of soundscape studies. The project was closely associated with R. Murray Schafer’s work at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Schafer’s influential role in popularizing the term “soundscape” and his emphasis on preserving natural sounds indicate his connection to this initiative24.

The WSP approached soundscapes as important cultural and ecological resources worthy of documentation and conservation. This perspective aligned with Schafer’s concept of “ear cleaning” and his concern about the increasing dominance of human-generated sounds in modern environments4. The project likely involved systematic recording and analysis of various soundscapes, establishing methodologies that would influence later research in the field.

The project’s work contributed to growing awareness of soundscapes as components of environmental and cultural heritage. By documenting acoustic environments that were changing or disappearing due to urbanization and industrialization, the WSP helped establish the importance of preserving diverse soundscapes. This conservationist approach continues to influence contemporary soundscape ecology, which recognizes the “preservation of natural soundscapes” as a recognized conservation goal1.

Although comprehensive details about the World Soundscape Project’s specific activities and achievements are not fully captured in the search results, its influence can be inferred from the continuing references to Schafer’s work and the development of systematic approaches to studying and documenting soundscapes that followed from early initiatives in this field.

Soundscape Ecology in Art and Design

The relationship between soundscape ecology and creative practices has grown increasingly significant in recent decades, with sound art emerging as a powerful medium for ecological expression and awareness. Since the early 2000s, a growing movement of sound artists has engaged with pressing environmental issues such as biodiversity loss, sustainability, and climate change7. This environmentally concerned sound art, sometimes termed “ecological sound art,” represents an important artistic response to ecological challenges, though it has yet to achieve the recognition enjoyed by comparable environmentalist practices in other art forms7.

Ecological sound art draws from soundscape ecology’s scientific understanding while employing artistic methods to create affective experiences that foster environmental awareness. This approach recognizes that sound offers unique pathways for engaging with ecological relationships that might remain abstract or invisible when presented through visual or textual means. Sound art can make tangible the subtle changes in acoustic environments that signal broader ecological shifts, creating powerful sensory experiences that connect audiences to environmental concerns.

The connection between soundscape ecology and design extends beyond purely artistic expressions to include practical applications in fields such as architecture, urban planning, and product design. Understanding the acoustic dimensions of environments enables designers to create spaces and objects that contribute positively to soundscapes rather than generating disruptive noise. This acoustic awareness in design represents an important application of soundscape ecology principles to everyday environments.

Scholars have noted a “fundamental accord” between contemporary ecological theory and the ways we experience and relate to sound art7. Both emphasize interconnection, immersion, and dynamic relationships rather than isolated objects or static conditions. This alignment suggests that ecological sound art represents not just a new field of sound arts practice but a particularly powerful form of ecological art that can foster new ways of thinking about and relating to the environment. The experiential, time-based nature of sound makes it especially suited to expressing ecological processes and relationships that unfold over time and across complex networks of connection.

Conclusion

Soundscape ecology has emerged as a vital interdisciplinary field that bridges scientific understanding, cultural awareness, and artistic practice. By studying the acoustic relationships between organisms and their environments, researchers have revealed the complex ways sound shapes ecological processes and human experiences. The field’s development from its early foundations in the work of pioneers like R. Murray Schafer and Barry Truax to contemporary research and creative applications demonstrates its continuing relevance to environmental science and cultural studies.

The categorization of sounds into biophony, geophony, and anthropophony provides a framework for understanding how different acoustic elements interact within environments and how these interactions have changed over time. Growing concerns about noise pollution and the increasing dominance of human-generated sounds highlight the need for continued research and conservation efforts focused on soundscapes. As soundscape ecology continues to evolve, it offers valuable insights for addressing ecological challenges and enriching our understanding of how sound connects us to the living world.

The growing movement of ecological sound art represents a promising development that extends soundscape ecology’s influence into creative and cultural domains. By engaging audiences through immersive sonic experiences, artists can foster ecological awareness and new modes of environmental thinking. This convergence of scientific understanding and artistic practice suggests that soundscape ecology will continue to develop in ways that bridge disciplinary boundaries and contribute to both environmental conservation and cultural innovation. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, the study and preservation of soundscapes offers a unique perspective that enhances our capacity to listen to, understand, and respond to a changing world.

Educational Sources

Center for Global Soundscapes The Center for Global Soundscapes’ mission is to support discovery, learning and engagement activities that lead to the preservation of Earth’s natural acoustic heritage.

Catalogue of Soundscape Intervention A soundscape intervention constitutes a site-specific strategy aimed at either preserving or enhancing an auditory environment. A wide array of potential interventions exists for designing soundscapes, encompassing micro-scale initiatives within specific locales such as parks, to extensive projects affecting entire urban districts. These interventions are associated with various objectives, including the diminution of undesirable noise, the incorporation of agreeable sounds for masking purposes, and the conservation of soundmarks that represent local identity.

WORLD SOUNDSCAPE PROJECT The official WSP website.

References

Footnotes

-

Soundscape ecology - Wikipedia ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10

-

Soundscape and acoustic ecology: The music of a changing world - earth.fm ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Southworth, Michael (1969). “The Sonic Environment of Cities”. Environment and Behavior. 1 (1): 49–70. ↩

-

Principles of Soundscape Ecology: Discovering Our Sonic World, Pijanowski ↩

-

Gilmurray, J. (2017). Ecological Sound Art: Steps towards a new field. Organised Sound, 22(1), 32–41. doi:10.1017/S1355771816000315 ↩ ↩2 ↩3